This story about ’90s teen surf sensation Shane Herring ran in ASL a few years ago, but was heavily edited. Here is the original “director’s cut”.

AUSTRALIA DAY WITH HERRO

By Tim Baker

When you’re an ex-pro surfer trying to get your life back on track, the last thing you need is a visit from a surfing magazine

When you’re an ex-pro surfer trying to get your life back on track, the last thing you need is a visit from a surfing magazine

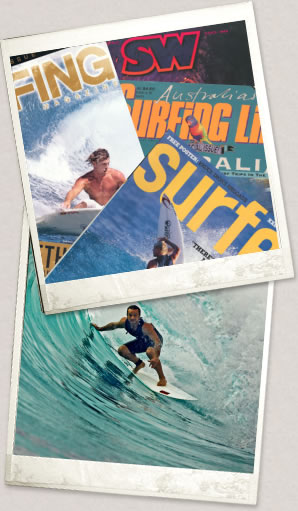

First up, a confession. I’ve always harboured a sense of guilt over Shane Herring’s premature demise from the pro tour. When the young, freckly, Dee Why natural footer defeated the all-conquering Kelly Slater in the final of the Coke Classic at Narrabeen in 1992, a veritable media stampede proclaimed him our great, red-haired hope to take on the American wonderchild.

ASL promptly whacked Herro on the cover, alongside the great Michael Peterson (also profiled in that issue), and dubbed them, “Our greatest legend & our newest star.” Somehow, in the subsequent years, as over-indulgence and personal turmoil harpooned Herro’s career propsects, I felt we’d placed some kind of weird surf mag curse on him. Comparisons to MP – both his brief but brilliant shooting star career path, and his battle with his own inner demons – have dogged Herro since.

I first met Shane when he was a barely pubescent 15-year-old at Grajagan, Indonesia. I’d never heard of him, but marvelled at this tiny kid who jumped straight off the boat and paddled determinedly into thumping eight to 10 foot, shallow, reef bottom barrels. It seemed almost prophetic when I happened to take a holiday snap of him at the dining table one night, with a can of Bingtang between two slices of bread, about to take a huge bite out of his beer sandwich.

Fast forward 18 years, Australia Day, 2005, and I track Herro down to a little, blonde brick duplex in the back blocks of Lennox Head, living with his childhood Dee Why mate, Joel.

Herro hasn’t surfed for a while, doesn’t even own a board. He’s nursing a broken collar bone, courtesy of a drunken wrestle with a few pit bulls, owned by his old pro tour partner in mayhem, Jeremy Byles.

“I reckon one of them tripped me over, I’m sure of it,” says Herro, thoughtfully. “I fell on this fucking tree, just went bang, broke me collar bone.” How’s life? What he’s he been up to, I ask? “I just struggle along like everyone else,” he says quietly. “I battle my demons every day.”

His once sun-bleached blonde locks are copper red and cropped short, he’s pale-skinned, carrying a few pounds, with a bit of fuzzy facial hair. It’s obviously a while since his last visit to the dentist. With his manic comic manner, he reminds me of Robin Williams, the actor.

He’s getting over a bout of pancreatitis, the same debilitating ailment that recently took down ex-Labour leader Mark Latham. But he seems otherwise well, happy for the company and keen for a chat. Herro’s an intelligent guy, who’s over-active mind has sometimes been his curse. He presents an eloquent case that – as he is no longer sponsored – we should offer some sort of incentive to do an interview, and he skilfully negotiates the fee of a carton of Coopers.

The house is simply but neatly furnished, collages of surf magazine pictures stuck on the walls, a few potted plants by the front door, a foam box of soil and wheat seeds, where Joel’s cultivating a crop of wheatgrass as a health tonic for his old mate. Shane’s playing Nick Cave when we arrive, then replaces it with vintage INXS, the Kick album, as if setting a mood. “Love me old INXS,” he grins.

We settle on a bench in the frontyard, crack the first Coopers before the clock’s struck midday, and roll the tape. Herro’s in turns funny, articulate, insightful, esoteric, and never shows a trace of bitterness about his well-publicised topple from pro surfing stardom. Did things just happen too fast for him? “It was very fast, but then again when you train really hard it only takes three years I reckon,” he says, seriously. “I trained from 16 ‘til 20 and then I went in three years from 54th, 36th, then 4th, and then basically it was over. I went 22nd, 44th and off the tour. So, it was five years, it was in and out.”

What happened? “I stopped training so I sort of lost momentum and I went another direction with boards and stuff,” he offers. “It would have been great to stay on tour. I’m only 33, I could have still been there and still been in the top 50 or whatever, earning money and stuff, but as it goes it doesn’t matter. That’s the way it went … I do think about that a lot, but I took too much shit, and the consequences are, if you waste yourself you’ll end up losing what you’ve got. For kids, you’ve got to watch your drinking and watch your intake of substances and stuff because it can wear you down and you’ll end up losing what you’ve got, and you won’t even know you’ve lost it until you get older.”

He says all this matter-of-factly, without self-pity, and talks of those pro tour days with nothing but fondess. “It was fantastic. It was a big party for five years,” he reminisces. “And the lead up to it from about16, 17 years of age, meeting Occy for the first time at 17, which was 18 years ago.” He marvels at time’s swift passage. “Surfing with him was a blow out at 17. I stole one of his dreadlocks off him one night, when he was asleep, had it in my drawer for years.”

He recalls it all with a vivid spark, almost relieved to be transported back in time to those exciting days. Training with Terry Day, alongside Damien Hardman when he won his first world title in ‘87, staying and surfing with Tom Carroll in France and getting advice from the master himself, competing against boyhood heroes like Gary Elkerton and Robbie Bain, wild times with tour buddies Shane Powell, Nick Wood, Robbie Page, and Cheyne Horan, watching Curren’s comeback when he won the world title through the trials in ‘90. He can still recall one Curren cutback at Santa Cruz – “It was unbelievable. He did this cutback, you could talk to anyone who saw it. It was on an eight foot wave, he went from the top of the wave on a 6’9”, beautiful surfboard, with his hand in the wall, and drove it on a vertically axis from the top, not a cutback, straight down.” He shakes his head. “No one thought he’d make it. He just pulled it off.”

Was it a touch surreal, for a teenager from Dee Why, to suddenly find himself amid his surfing heroes? “Yeah, definitely, because they were the ultimate heroes. Now there’s a lot more, but back then there was just the top 16, and that was it. Nowadays it’s the 44 and then you’ve got all the WQS guys. You’ve got 80 of them now. Back then it was just the top 16.”

What does he recall about that fateful Coke Classic, that abruptly turned his world upside down?

“I just cruised through every heat. I didn’t care if I won,” he says. “Oh, I was defnitely amping to win but I was in a zone … I think I remember people sort of going against me in the final, saying there was no way I could beat him, but it was only two foot right handers and they were my best waves, growing up on Dee Why shorebreaks, so I was fine with that.”

When the final hooter sounded, Kelly jumped off his board and tackled Herro in a headlock, and held him underwater. It looked like playful high spirits between two friends, but even from shore you could sense Kelly was more upset than he was letting on. “I think he was pissed off, I think so,” says Shane. “Because that was his first final and my first final, my first and only final, and I beat him. He wasn’t happy. It may have upset his script but not in the long run.”

Did he feel the pressure, the weight of the nation’s surfing pride heaped on his slim shoulders, to stop the Slater juggernaut?

“Not at all, because Kelly’s way better than me, a way better surfer than me, I thought anyway. Even Powelly, Powelly’s a way better surfer than me, still.” One thing Herro’s determined to clear up is the great Banana Board controversy – the radically curved and full concave boards that shaper Greg Webber produced specifically to help Herro take on Slater. The revolutionary boards appeared to work wonderfully in hollow, sucky beachbreaks, but struggled in fat waves or long, down the line points. At times, Webber’s been blamed for Herring’s untimely demise, by sending him off on this extreme design tangent. Herro scoffs at the suggestion.

“Those banana boards enabled me to turn in places other people couldn’t turn,” says Shane. “The old guys couldn’t match it, and they were seeing something different and something new and that’s why I got where I got. So Greg changed surfing to what it is now, I reckon, and it changed my surfing too … Now kids are riding barrel concaves with a lot of curve and their spinning around and they’re doing all that, and that was 13 years ago. And Greg Webber did do that so good on him.”

What’s the lesson for pro surfing and the surf industry from Herro’s career? Do we need to provide more mentorship and guidance, for young, suddenly cashed up pro surfers sent out into the world? Herro shirks none of the blame for his own undoing. “I’m from Dee Why and we’re pretty much mongrels down there, so I just went it on my own,” he says. “You don’t know what you’ve got unitl it’s gone, you know. I wasn’t that strong … Hopefully you’ve got people behind you to help you along and slap you around the head if you start losing it.”

Does he blame the media for contributing to his undoing? “I don’t care what anyone wrote about me,” he declares. “’Oh, he’s lost it, fucking loser.’ Yeah, I lost it a couple of times, but you go through stages. I wasn’t feeling good last week, but I’m feeling good this week,” he laughs. “That’s the problem with the media, it can be quite exploitative, but that’s the way it is. It can make or break you.”

Any advice for youngsters finding their way through the maze? “Keep your mouth shut and just surf.”

At the peak of his earnings, Herro was pocketing a tidy $140,000 a year, and lived of his savings for a few years after the sponsorship bubble burst, and now has virtually nothing material to show for it – other than a couple of packs of clothes a year from a faithful old Quiksilver contact.

When the sunny pro tour nostalgia runs out dark clouds seem to gather and Shane becomes vague and troubled and difficult to understand at times.

“There’s controlled and there’s uncontrolled. I don’t know what I’m trying to say, “ Herro announces at one point. “Do you want to contribute to the controlled side of things or do you want to be an anarchist? I don’t know … but if you’re on the outside then you’re not going to get much work are you?”

Maybe it’s just the Coopers kicking in, because from here in on things grow decidedly hazy. The case disappears faster than seems feasible and Shane and I are soon embroiled in a strange, hybrid Tai Chi and Yoga demonstration – though it is unclear which of us is teacher and which is student. It occurs to me, it is probably in circumstances similar to this that Shane broke his collarbone.

Joel’s taking this all in curiously, with a touch of concern, then grows increasingly annoyed. “I’ve kept him off the drink for six days until you guys showed up,” he reports. His plans for Herro’s rescue by wheatgrass seem to have been dashed by the dastardly surf media that have repeatedly heralded his undoing, and my conscience is more rattled than ever. Yet amid the mayhem, the darkness seems to pass. Herro asks me if I can see his demon, hovering above one shoulder, watching over us, if I’ve noticed that it seems to be shrinking? I can’t say I have, though he does seem to be in a particularly good mood again.

Joel’s concerned that we might be encouraging bad habits, all this nostalgia and re-living old glories. “He doesn’t even surf, mate,” he heckles. Joel’s the one we should be doing a story on, he argues. Joel’s only 25, would only have been 12 or 13 when Herro won the Coke. “I got good trying to be as good as him,” Joel explains. Now, he finds himself trying to ressurect his fallen idol and manage this increasingly raucous media engagement.

And then … the case runs out. Joel and Herro have each stashed an emergency stubbie away secretly and retrieve them triumphantly. Photographer Hilton is looking at me anxiously and motioning towards the door, as if a swift getaway may be in order. Herro produces an old Sky single fin shaped by Bob MacTavish from his bedroom, and announces that he is now ready to go surfing. Joel and Hilton shout him down, tell him he’ll drown in his condition and he seems briefly crestfallen that a fairytale comeback is not going to happen right now. Hilton and I edge towards the door, but Herro is on to us, arguing that an additonal fee might be in order given the depth and frankness of the interview he has given. I manage to get to the car only $20 poorer and Herro is still celebrating in the frontyard as we drive off, waving the redback gleefully.

stumbled upon Shane doing ding repair in Bylesy’s used surfboard shop outside Byron Bay. After defeating Kelly Slater at the Coke Classic at Narrabeen in 1992, Shane Herring was proclaimed the greatest Australian surfer since Michael Peterson. But cover shots, a six-figure salary and endless parties eventually undid the focus and determination of this rising star. In a post Andy Irons world, Shane’s story serves as a cautionary tale for up-and-coming surfers regarding the dangerous effects fame and money can have on fragile young egos. Over a cigarette and bottle of wine, Shane shares some of his struggles and life lessons in this episode of Korduroy’s InnerViews.

Shane Herring – InnerViews from www.KORDUROY.tv on Vimeo.

KORDUROY.tv

Camera/Edit:

Cyrus Sutton

Erik Derman

Surf Footage by Chris Bystrom from Oz on Fire Vol. 1 NSW – 1991

Check out more of his epic footage at chrisbystrom.com

Pretty sad…

But on the other hand He seems to be rather happy…